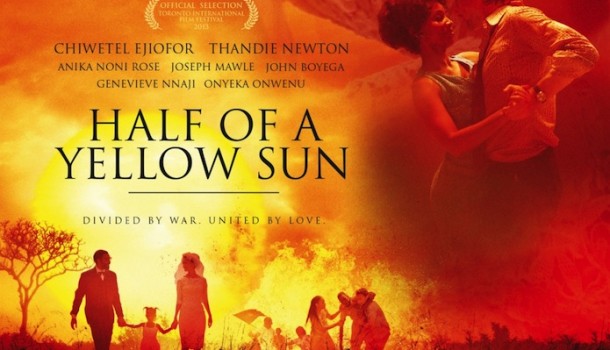

TITLE: HALF OF A YELLOW SUN

FILM BY: BIYI BANDELE

DIRECTOR: BIYI BANDELE

TIME: ONE HUNDRED AND ELEVEN MINUTES

REVIEWER: SALAWU OLAJIDE

If you are yet to read Chimamanda Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, then Biyi Bandele’s movie is one you should not miss. The film is stellar, full of scenes picked out of Chimamanda Adichie’s novel. It is an intellectual adaptation of the novel set against the backdrop of newly birthed Nigeria delivered out of the colonial government of British Empire. Biyi Bandele has made a brilliant rendition of the Orange Prize winning novel into images that are reeling before us in a matter of few hours.

Biyi Bandele makes the film to course through convoluted paths the novel itself treks on. We have love but we also have vengeance and feminism staring us in the face. We have harmony through the political solidification of independence of sovereign Nigeria made up of multifarious ethnic groups. As we are dealing with nepotism, one of the evils that sneaks in with independence; we have the political construction left over by the British. But most importantly, we have Nigeria, the mere ‘child’ going through the teething path of coup d’etat, civil war, and ethnic bigotry. The Nigerian-born film director leaves this trajectory of artistic discourse of history by compressing the facts, but making us to see the whole through the web of characters, actions, and cinematographic pages presented to us.

The film starts from the independence ritual and uproar, with the English broadcaster giving us background information about the newly independent nation then voice of Miriam Makeba sends the soul down to attention that the film wishes to steal. Just after brief quietness the new nation meets its first boulder through the coup de’tat, masterfully planned by General Nzeogwu, the story we learn to hear through Odenigbo’s radio. Instead of the vast lane of words, Biyi has disseminated this tragedy through the simple phrases of the radio. This might be inadequate a piece of information because of the dependency on images in film making, but the acrimonious ethnic tension it has justifiably captured through Odenigbo’s simple gadget is also an artistic effect. Issues are lapping over issues in this grand production achievement by Biyi Bandele. We should know the lens through which this geographical harness is perceived by the British through the encounter made available in the independence celebration meeting when one of the British runs a brisk comment on the three dominant ethnic groups:

“The Hausa in the North are a dignified lot.”

“The Yoruba are rather jolly as well as being first-rate lickspittle.”

“And the Igbo are…surly and money loving.”

The interruption of Kainene, younger sister of Olanna gives us a perfect completion of commercial domineering perspective in which the easterners are viewed in the country. This does not fail to throw light into who Kainene is, as a socialite who charges towards fashion, being also from upper rung of the society. And she does not fail likewise to reek of capitalism.

The film does not shoo away the imposing presence of love throughout its scenes. Odenigbo, played by Twelve Years A Slave protagonist Chiwetel Ejiofor, is seen in his deep affection with Olanna (Thandie Newton). He could not resist her slim athletic body even after his clandestine affair with Amala, the village girl. This stronghold of love sees the two achieving their climactic achievement of love and marriage, despite the air reeking of the foul smell of death and war. And the bond of love, even interracially cannot be debunked when we see Richard searching for his lover Kainene after the war. But on the opposite, vengeance sits owlishly after Odenigbo declares of his sexcapade with Amala as Olanna does not fail to play Shylock and goes on to have sex with Richard. This issue is also reflected in the counter coup.

Sometimes, the interruption of documented videos of Ojukwu’s speech, and the recount of the narrator we meet at the inception of the film, quadruples the film as a faction. It goes beyond a mere recall of history to the history itself. As emphasised earlier, the film sometimes fails to give us the image but instead reports the story through the third party. This, one can see when Mama dies during the war and her death is only made available through a third party. Even Kainene herself can be seen in the same light as her disappearance for a business trip will mark her end.

Each character does not fail to castigate the other for the ethnic failure. Miss Adebayo (Genevieve Nnaji) calls Odenigbo a ‘hopeless tribalist’. Indeed? Odenigbo does quickly make his own reproach by questioning the Yoruba for their silence during the coup and Igbo massacre in the North: “Didn’t your chief go North to thank the Emirs for sparing their people?” This is an ethnic rivalry and discord bedevilling the nation till date, blaming the other for the failure on ground. It is not only the revolution, the labour strike, and secession that are in the mind of the protagonist, Odenigbo, but also his identity, as he argues: “But I was Igbo before the white man came.”

The film is a constellation of scenes piled up through the flaws, hopes, and aspirations of Nigeria as a whole. The fall of Olanna from upper sect of the society to a mere domestic woman facing the searing effect of a failed independent nation is symbolic, and also littering along are different issues of humanity, individual, gender, politics and history, giving the film nothing but a thunderous credit.

About the Writer: Salawu Olajide is a graduate of Obafemi Awolowo University, Ife. He writes poems, short stories, and watches a lot of TV. He listens to dadakuada music at his leisure time.