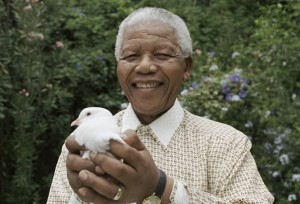

Today we are sad to announce the death of a notable icon, President Rolihlahla Nelson Mandela. He passed away at the enviable age of 95. He was a most influential entity, an altruistic leader, a beacon of freedom, a man whose accolades span about 250 awards, including the 1993 Nobel Peace prize, the US Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Soviet Order of Lenin. He is the President of a country; he is a role model to nations. It is a loss that words cannot fully express, and even though we are grateful for his long regime on earth, one cannot shrug away the heavy shroud of sadness that comes with losing one so great, and of an ilk so rare.

Mandela’s life story is the stuff of legends. It is so easy, with all he has achieved, to forget that he is human. Oftentimes  when one looks at the life of such a great person, it becomes difficult to empathise, and you are inclined to place them on a high shelf where you can admire but not relate to them, because the person that they are is so different from the notion you hold of yourself. Sometimes the celebrated individual may indeed come from more privileged circumstances than you, thereby making it appear relatively easy for them. Not so for Mandela, who is fondly called Madiba by his people.

when one looks at the life of such a great person, it becomes difficult to empathise, and you are inclined to place them on a high shelf where you can admire but not relate to them, because the person that they are is so different from the notion you hold of yourself. Sometimes the celebrated individual may indeed come from more privileged circumstances than you, thereby making it appear relatively easy for them. Not so for Mandela, who is fondly called Madiba by his people.

You see, Mandela is no stranger to failure, or to shame, or to plain old irascibility. As a child, his given name was Rolihlahla, which literally translates to ‘the branch that fell off the tree’ or in short, troublemaker. His father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, was of royal blood and councillor to the monarch; he had been appointed to the position in 1915, after his predecessor was accused of corruption by a governing white magistrate. However, his father’s high hopes of being made chief were cut short, when he too, was sacked for corruption. Unable to take the shame, his family had to leave the village. To shield him from the disgrace, Mandela was told that his father had lost his job for standing up to the magistrate’s unreasonable demands. They moved to Qunu, and his father later moved in with him. When he died of what Mandela believed to be lung cancer, he lamented his demise and later stated that he believed he inherited his father’s “proud rebelliousness” and “stubborn sense of fairness.”

This drive fuelled all his decisions and choices, coupled with all the morals and lessons he learnt from attending Methodist church every Sunday of his early life. He developed a love of African history, listening to the tales told by elderly visitors to the palace, and he considered the European colonialists as benefactors, not oppressors. He attended very good schools and took up many hobbies, including acting, gardening, sports and ballroom dancing. A member of the Students Christian Association, he gave Bible classes in the local community, and became a vocal supporter of the British war effort when the Second World War broke out. Although having friends connected to the African National Congress (ANC) and the anti-imperialist movement, Mandela avoided any involvement. At the end of his first year he became involved in a Students’ Representative Council (SRC) boycott against the quality of food, for which he was temporarily suspended from the university; he left without receiving a degree.

This drive fuelled all his decisions and choices, coupled with all the morals and lessons he learnt from attending Methodist church every Sunday of his early life. He developed a love of African history, listening to the tales told by elderly visitors to the palace, and he considered the European colonialists as benefactors, not oppressors. He attended very good schools and took up many hobbies, including acting, gardening, sports and ballroom dancing. A member of the Students Christian Association, he gave Bible classes in the local community, and became a vocal supporter of the British war effort when the Second World War broke out. Although having friends connected to the African National Congress (ANC) and the anti-imperialist movement, Mandela avoided any involvement. At the end of his first year he became involved in a Students’ Representative Council (SRC) boycott against the quality of food, for which he was temporarily suspended from the university; he left without receiving a degree.

Decision after decision can be seen strewn in his life, as he went back home and through a series of events, settled down to be a family man. Having been raised in a predominantly leadership atmosphere, it almost seemed that Mandela was taking pains to not be cast in any leading role whatsoever. However, it was at this point in his life that he became a rebel to the leading political party, struggling with their ideals as they warred with his moral beliefs and the teachings of Karl Marx and Jawarhalal Nehru. He took up the fight against racial segregation and apartheid and lost his wife, his children, and the support of his mother, but there was no stopping the train once the engine was started. Even prison could not subdue him. Mandela spent the better part of his life behind bars, effecting change and talking to dignitaries, trying to get the President at the time, P. W. Botha, to review the legislation and abolish apartheid. Botha didn’t listen, but his successor did; and in turn he and F. W. de Klerk were able to restore peace to South Africa.

We duff our hats to you, sir. We are sad that you are no longer with us, but with this sadness comes a bittersweet hope that even though the candle of your life has been put out, it’s flame has rekindled the hopes and dreams of many who live free today because you lived and you loved. May your gentle soul rest in perfect peace.