As a town, Agbarha Otor doesn’t strike one as significant; at best, it seems like a stop on the way to or from Ughelli, a larger urban center to its South West. But its inhabitants aren’t bothered by this. They rest in the pride that a kinsman of theirs founded one of Nigeria’s largest and long-surviving businesses.

That business is the Ibru Organization, a large indigenous conglomerate that’s half a century old. The Ibrus have their fingers in multiple industries: shipping, aviation, agriculture, finance, hospitality, and oil and gas. But the Ibru Organization isn’t just the boast of a single region. With commercial interests worth billions of dollars spread over Nigeria, it has become a driver of growth for the many communities in which it is active.

The Beginning: Winning with Frozen Fish

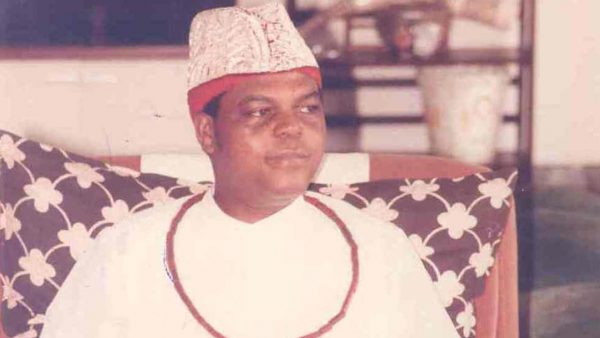

The Ibru Organization has an unlikely beginning. Michael Ibru, its founder, was born in 1930 to Peter Ibru, a missionary, and Janet Ibru, a trader. While he did get formal education, the career path laid out for him at an early age wasn’t of the business mogul variety. He took up a job at the United Africa Company (UAC) in 1951, after completing secondary school education.

But five years later, he decided to take a different road. At age 24, he left the UAC and partnered with an English businessman to start a trading company (the name of the venture, Laibru, was derived from the surnames of both men, ‘Ibru’ and ‘Large’).

In 1957, Ibru took an even bolder step. He dared to pioneer the sale of frozen fish in Nigeria. It’s hard for us to understand how odd this would have been at the time. Today, our markets are awash with frozen seafood. But in those days, fresh fish was all that was available. Ibru’s idea seemed so outlandish to local people, that other traders called his product “mortuary fish.”

Despite initial failures, he pressed on with his plan. He believed that the country would embrace the product at some point in the future when power was widely distributed enough to make the cold storage of fish commonplace. He wanted to have a first entrant’s advantage in that future market. And he eventually did.

In the end, Ibru Seafood was a hit. Ten years later, the company had more than 20 trawlers fishing on the oceans, and cold rooms in Lagos which stored the large hauls of fish they caught.

Read about other family businesses in Nigeria here

Expansion: the Making of a Conglomerate

The Ibru conglomerate began to take shape. Ibru diversified his portfolio to include a palm oil plantation in old Bendel State and an 800-hectare fruit farm. His concerns also extended into petroleum distribution when that industry strengthened in Nigeria, as well as transportation and real estate.

Other members of the Ibru family emerged to steer the organization’s ship with its founder. Alex Ibru, one of Michael’s brothers, was in charge of Rutam Motors, a fleet maintenance venture which also managed the Ibru Company’s own fleet. He later joined forces with a number of journalists to found the Guardian Newspapers in 1983. Another of the Ibru brothers, Goodie Ibru, was chairman of Ikeja Hotels, a position he held until he stepped down in 2017.

Cecilia Ibru, Michael’s wife, started her career at the Ibru Organization, where she was a project director; she rose to become its international finance coordinator, before venturing into the Nigerian banking industry.

Mr. Oskar Ibru, who was Mr. Ibru’s son, became involved with the organization in the 1980s and took charge of substantial portions of its operations in the 1990s. He succeeded Mr. Ibru after the latter passed on in 2016.

The Legacy of the Ibru Organization

From its beginnings at the fish markets of Lagos, the Ibru Organization grew to employ thousands of persons in different industries at the turn of the millennium. Although it has had its tough times, it continues to survive and thrive.

As is the case with every forward-looking conglomerate, it’s possible that new turns in this organization’s story lie ahead. Its next generation of leaders may have even more market-defining moves up their sleeves. Time will tell.

Featured image source: The Guardian NG