Nigeria, home to one in five Africans and with over 100 million people as of 2006, was once Africa’s most indebted nation. However, on 21st April 2006, as part of a chain of strategies deployed by experts to get some breathing space, Nigeria made a final payment to the 19-nation-strong Paris Club of Creditors which helped it to strike off $18 billion of debt out of the $36 billion external debt. This final payment was a huge relief on government officials and on the fortunes of the nation; even ordinary Nigerians celebrated it in varying capacities.

For much of the time since the return to 4th Republic democracy in 1999, Nigeria had been struggling with insurmountable debt which affected largely its monetary and fiscal planning/policies. President Olusegun Obasanjo made a promise not to spend his time in office paying off crippling debt. Nigeria barely had much to save for capital projects after having to pay interests and part of the principal -this largely affected the rate of growth the economy experienced between 1999 and 2006.

Although Nigeria did not receive any fresh loans since 1992, it has managed to repay $8bn debt since then. The team representing Nigeria in the case, therefore, centred the campaign for debt relief on the fact that most of the money it received was lent to corrupt military dictators. This fact was also quite obvious to foreign banks and governments but they still went ahead to demand stricter measures of compliance just to validate Nigeria’s seriousness.

Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, who was the Minister of Finance and also doubled as the head of Nigeria’s economic team, had led a campaign which comprised the likes of Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) Governor, Professor Charles Soludo, and vastly supported by President Obasanjo, to get a large portion of the accumulated debt written off.

The initial debt relief terms, which was based on the so-called Naples Terms, – equivalent to a 67% reduction on the face value of debt, is usually applied to debts of poorest nations. Eventually, many world leaders sympathized with the case of Nigeria and the strong case presented and, in October 2005, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced a final agreement for debt relief worth $18 billion and an overall reduction of Nigeria’s debt stock by $30 billion. The IMF remarked that the debt relief would be significant, and allow for long-term debt sustainability.

Perhaps, because of the regular oil revenues which seemed to be large enough, Nigeria, for long, slipped through the cracks of debt relief programs which other poor nations benefitted from. There was also a lingering

Having satisfied all the conditions, Nigeria qualified for the largesse which many other indebted but struggling developing countries in the world had enjoyed. The deal was completed on April 21, 2006, and its books were cleared of all Paris Club debt.

Nigeria’s debt relief deal was therefore historic. Although, the short-term financial windfall was modest largely because Obasanjo and his cabinet could no longer continue to retain the seat in government; his 2nd term had to end in just about a year from the date the debt forgiveness took effect.

As we have largely witnessed over these past few years, from that remarkable date of debt write-off, leaders who took over after Obasanjo did not fully take advantage of the relief the debt forgiveness brought. Nigeria has found it hard to consolidate on the gains from the debt deal by pushing forward with economic and other extant reforms while ensuring that the benefits from the debt relief are shared with the citizenry. Many years after the largely celebrated debt forgiveness, Nigeria remained the world’s 7th largest oil exporter, yet, she was still one of the poorest in Africa and in the world.

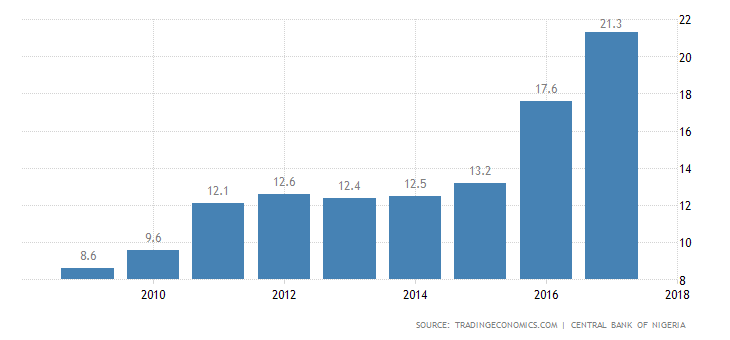

Nigeria’s foreign debt profile is fast rising again. All hands must therefore be on deck to ensure that our debt-loving leaders do not cause the future of the nation at large the misfortune of heavy debt burden once again.

Featured image source: Trading Economics